Child Trafficking Remains an Issue in Southeastern Massachusetts – 10 more points we need you to know

January 20, 2022

This article, it’s data and information included was written with input and information provided by team members from Children’s Cove, the Bristol County Children’s Advocacy Center, and the Plymouth County Children’s Advocacy Center.

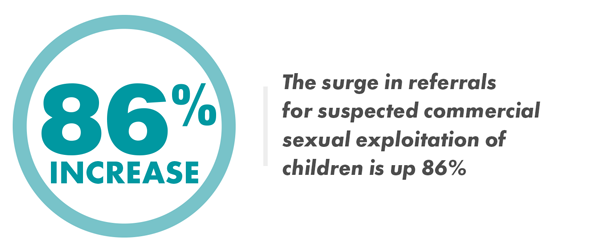

In 2021, the Children’s Advocacy Centers for Cape Cod & the Islands, Bristol County and Plymouth County held response meetings and coordinated support services to nearly 300 child victims of human trafficking. In nearly 90% of these cases there was an online element related to the exploitation, meaning, the exploitation took place online OR there was specific communication, planning or exchange which took place online. Children in our communities, including Hyannis, Westport, Fall River, Hingham, Brockton, Mashpee, Plymouth, and Dartmouth, were identified as victims of sexual exploitation and human trafficking. Each of these Child Advocacy Centers (CACs) in southeastern Massachusetts work collaboratively with every branch of law enforcement and child protective services to provide a coordinated response to child trafficking. With an increasing risk to children in online spaces, we want to inform the community of the trends we have seen over the last year. This article aims to demystify the terms and issues, where these risks unfold, and what parents and caregivers in the community can do to reduce the risk of exploitation online.

1. The Definition of Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children (CSEC)

Human trafficking is widely defined as “a crime that involves exploiting a person for labor, services, or commercial sex.” Massachusetts state law further defines the trafficking of children as the Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children (CSEC). The CACs of Massachusetts recognize that CSEC occurs when a person under the age of 18 engages, agrees to engage, or offers to engage in sexual conduct with another person in return for a fee or an exchange of food, shelter, clothing, education, or care. Child sexual abuse material (child pornography) can also be considered a form of trafficking.

2. Online Exploitation is More than Just a Photo

Often, when people hear the term online exploitation, they may think it is solely referring to the sending or receiving of nude images of individuals under 18. Correctly, yes, that is a form of online exploitation where a child’s image can then be captured and sold, traded, or shared indefinitely on the internet. However, Child Sexual Abuse Material can be far more than that. Once a child has discovered the person has saved the image, they may be manipulated, threatened or exploited to produce more (often increasingly graphic) images or ultimately meet in person where they become physically exploited. The person receiving the image may be receiving some type of financial gain from their exploitation, or use it to trade with other exploiters. The shame, embarrassment and fear children feel upon learning the person they are engaging with online is not the person they claimed to be reduces the instances where they will ask for help from a trusted adult. What can start as one single image can quickly spiral out of control to a place they never would have found themselves otherwise.

3. Exchange is Something of Value to the Child, Not Everyone

So often parents and professionals alike only think of an exchange being money. Money is the least often exchanged item of value for children who are victimized. And, as a reminder, an exchange does not need to take place, only be offered. Digital assets and currencies in video games and mobile apps as well as substances not regularly available to children (such as nicotine products including vapes) have rapidly increased as items of value in our region. At times, something more personal is what is desired or valued; someone being their boyfriend or girlfriend, going to a party together they would never be invited to otherwise, etc. The feeling of being wanted, socially accepted, and loved is often the “exchange” or tool exploiters use most.

4. No Type of Access is “Safe”

If a child has access to an internet connection, they are at risk of exploitation. Across our region we have seen exploitation take place on parents’ computers, tablets and phones, as well as their own tablets, computers and phones. We also have seen exploitation take place on video game consoles, on school-based Chromebooks, tablets, and iPads and through apps associated with school use. Often, the fear or anxiety associated with risks for exploitation are when a child receives their own mobile phone. If parents and caregivers don’t keep their eyes on these devices and have regular conversations about safety on all internet enabled devices the opportunity for exploitation to happen in plain sight remains high.

5. The Top Culprits in the Digital World

Children can access nearly an unlimited number of apps, social media profiles, email accounts, and online exchanges such as CashApp, PayPal, and Venmo. These apps keep the evidence of exploitation hidden behind a mobile or internet-based device. If parents aren’t involved and regularly monitoring their children’s apps and internet enabled devices, this may be happening right in the same room. Staying up to date with what is trending in the digital world is as important for caregivers as it is for the youth who use them.

Over the last year the most prominent apps where exploitation has taken place, or has been discussed or coordinated were Snapchat, Discord, Facebook Messenger, Instagram, Chat Roulette, WhatsApp and Omegle. For parents and caregivers, understanding how these apps work, discussing safety rules online for these apps, and having your children show you how they use and access them is a good place to start. For resources about apps, how they are used, check out the parent resources on the Internet Matters website.

6. Apps on the Rise and Not Thought About

While the apps listed above have been a focus of issues and investigations over the last year, we are increasingly seeing more issues in newer apps. With TikTok being the most searched and rapidly growing social media and video sharing network since 2020, it has attracted everyone to its platform young and old alike. Children as young as 9 and 10 years old have found themselves in dangerous situation on the platform and as it has become more commonplace, parents and caregivers may have gotten more relaxed about safety associated with this app. This has also translated to video livestreaming apps and platforms like Facetime, Zoom, Skype, or messenger apps which allow livestreaming. Kids and teens may begin a streaming call with the belief that because it is happening in real time it cannot be captured or recorded, when in fact screen shots, sharing and recording is easier now more than ever. And, due to the nature of the streaming, there would be no record on behalf of the streaming service of what took place if it was recorded by a third-party app. Even apps designed specifically for kids and teens with safety in mind, such as Yubo, are targets for online predators and exploiters to infiltrate for the very fact it is supposed to be safe.

7. Exploitation is Normalized and Often Missed

“Sexting,” or sending sexually explicit text messages and images, has become a social norm for kids and teens. With the virtual world regularly intertwined in the real world, dating and sexual exploration regularly resides in online spaces. Sending a nude image to someone a child is interested in is as common as passing a note was pre-cell phone days. However, because of the commonality of it, the desensitization and normalization of one’s nude image is devalued. What was once a horrifying and embarrassing event of a sexual photograph or nude being sent to a group of people is now a common occurrence to little or no alarm. At times these images live right in the group chat of your child’s main friend group on their phone, the place you would never suspect would be an issue.

You must have the difficult conversations about online exploitation with your children and start when they are young.”

8. Prevention is Possible

When reading this list or learning about online exploitation, the first reaction for parents and caregivers is often “well, they just won’t have a phone or a computer, that’s it.” That is as realistic as saying a teen can’t have a car because some people drive recklessly, can’t play sports because of injuries, or go to parties because some people drink. The online and digital world is where most children learn, socialize, and engage. The same conversations about safety which are used for driving, sports and parties need to take place about being online. As a parent, you can have conversations with your children about body and online safety. You can set ground rules for internet usage and access. You can have the difficult conversations about online exploitation with your children and start when they are young. The more engaged you are with a child’s online life and the reality and risks; the more likely they will be to talk with you about issues they have.

9. Leave the Door Open

Even if you do have these conversations with your children, there is always the lingering fear from kids and teens if they mess up and tell you they will get in trouble. We know kids and teens will mess up, and we most definitely would like to take their phones and encase them in concrete and send them to the bottom of the ocean. However, what’s most important is that they know that your door is open for a calm, non-judgmental conversation so that if they do make a mistake, they can ask for help. If they do make a mistake or make a report that something happened to them: believe them, advocate for them, and focus on their health, wellness and safety with support from your local CAC.

10. If Your Child is Exploited Online

Remain calm, and don’t take quick action such as deleting images or messages; these may be important to effectively report and get help. Identify how, when and where this happened, where the images are now and who may have them (do not view them), and what app or platform (messenger, Snapchat, Kik, etc.) it was on? Contact your local police department, and you can reach out to your local Children’s Advocacy Center and ask what steps to take next. The National Center for Missing Children (NCMEC) has an incredible resource for parents to walk through how to have content removed from all major platforms in a streamlined process. If you see or suspect child sexual abuse material online or on social media, you can report it to NCMEC through their Cyber Tipline. You don’t need to know who an exploiter is; he or she can be unknown to you – what’s important is that you make the report.

If you have concerns that a child is being exploited, please report suspicious behaviors to your local CAC, law enforcement agency or file a report with the Department of Children and Families. All of these cases are screened and reviewed with a focus on safety in our community. If you are unsure of where to seek support, or what next steps to take, visit our Get Help page for more information.